'For the brave of heart and free of spirit': meet Kate Humble

SLICE OF LIFE #6 Talk about a quote that makes your heart sing… TV presenter Kate is as full of life-affirming sparkle as her (special) new book. Here she is – plus her not-to-be-missed Joyous Things

Loved by thousands of fans for her TV programmes giving armchair insight into bucolic rural life, Kate Humble has a zest for everything she does that’s so, well, zesty, it makes you want to jack in your humdrum life, escape to the country, stride through muddy fields in proper wellies and feel the wind in your hair. The reality isn’t all fluffy lambs and cooking legume-rich stews on the Aga, of course – although there’s some of that.

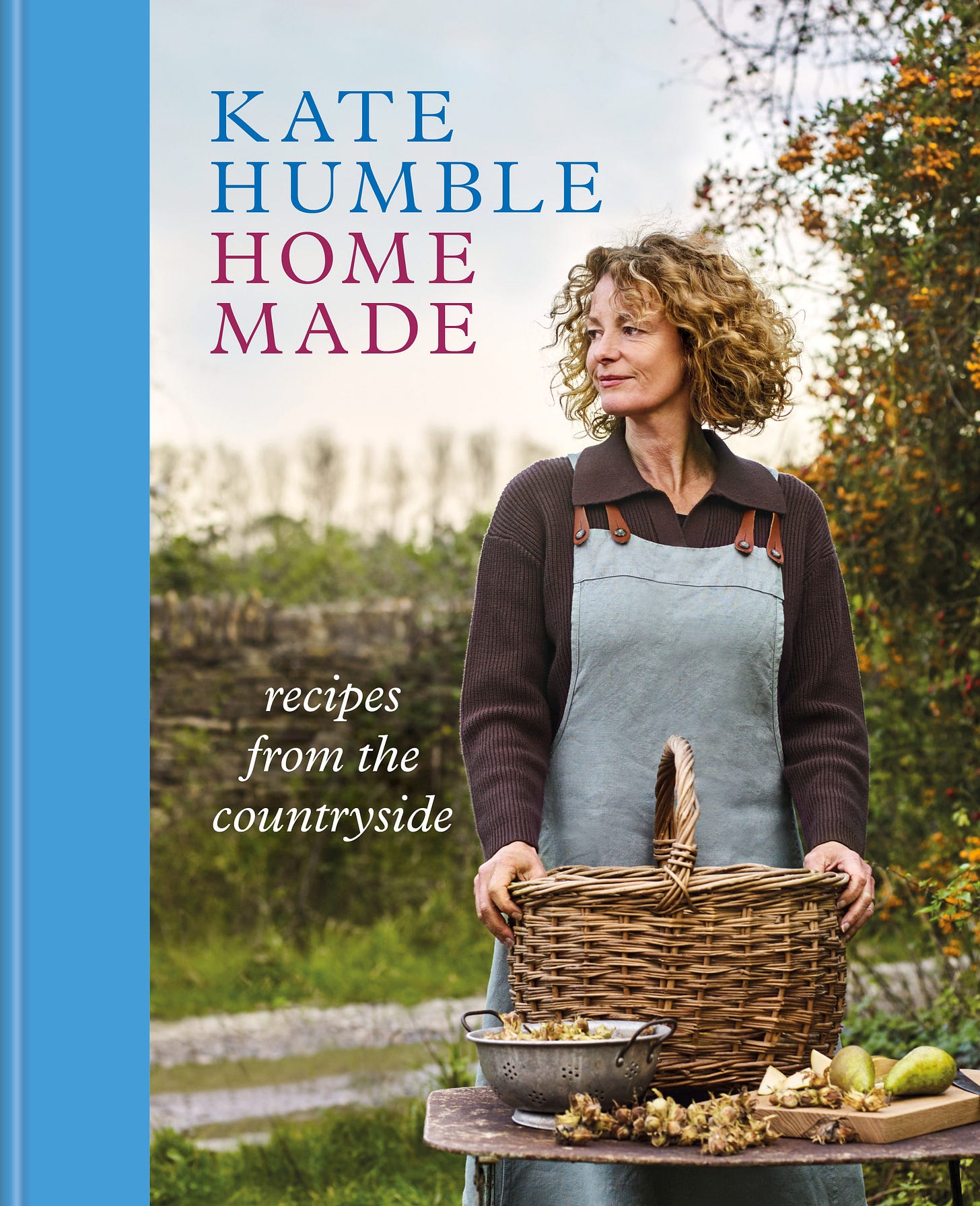

The quote at the top of this newsletter is writ large on the opening page of Kate’s life-affirming new book, Home Made, which celebrates the stories of people bucking the trend of our quick-fix, cheap-import, consumerist society. Stories of artisans who craft beautiful, practical objects by hand, lovingly and painstakingly. All the objects are related to food in some way – either the producing, the preparing, the eating or the serving of it: salt, boards, knives, aprons, plates, willow baskets, cheese, glasses, jam… The stories are interwoven with Kate’s recipes – recipes with universal appeal for their comforting simplicity.

The book is a beauty thanks to photographs by Andrew Montgomery, one of the UK’s finest photographers, who I commissioned for innumerable projects over the years when I was editing delicious. magazine. Andrew’s genius is his ability to capture a sense of place, a moment in time, an atmosphere. The photos are beautiful and timeless. That goes for his food pictures, too. And Kate’s philosophy – her belief that mistakes are crucial in shaping us, forming our character and making us more robust – shines out of every page.

These are the reasons Home Made has been sitting by my side of the bed for weeks as I keep returning to it, re-reading the stories, mulling over which recipe to make next as the season has migrated from late summer to autumn.

I couldn’t wait to meet Kate and find out more…

‘The legacy that matters is the imprint you leave on the earth when you’re gone’

Where do you think your brave, free spirit came from? We’re told right from the outset that we’re on a path. I was. My parents worked incredibly hard to give me the best education. Parents believe that’s the best start they can give their kids. In lots of ways they’re right, but mine sent me to a school they thought would give me the best prospects – very academic. All I learned was how to take exams. I was good at that, much to the annoyance of my teachers, as I didn’t do a lot of work.

School was a sausage machine on the way to Oxbridge. There was no deviating from that. I knew early on that wasn’t what I wanted to do and I didn’t enjoy that process of learning. I loved finding out about stuff because I’m nosy and curious, but I felt confined by the approach to learning. I left school with no intention of going to university, which was a great sadness for my parents. They had worked their guts out and I said, at 18, ‘I’m off.’

I did what I wasn’t channelled to do, and it was absolutely the right thing for me. I’m not particularly brave but I am free spirited. The bravery was in understanding where I would flourish. My mum would say, ‘That’s my daughter, she’s never done what she’s told.’

I recognise like-minded souls and I know it’s tough. I’ve always admired people who plough their own furrow.

Did that affect how you chose people to feature in your book? Yes! I wanted to write a book that’s as much about people as it is about food. When home economist Pooch (Anna), photographer Andrew and I were sitting around Pooch’s kitchen table deciding on who to feature, my rule was that everyone had to make a living from what they did. It couldn’t just be a hobby. And I wanted the book to be as much about those people as about food. It was a collaborative thing, which is how I love to work. Continuity is everything for me – especially as it’s so different from the world of TV.

The BBC series Back to the Land, screened back in 2018, was hugely popular because people dream of being brave and free of spirit but they can’t necessarily be that. It doesn’t stop them having a vicarious joy through others, though. That’s what Home Made celebrates.

Have your views on university changed? No. Your point of difference can be that you don’t do what everyone else does. You don’t have to start saddled with £40k worth of debt. I started making tea and sweeping floors. At one point, when I was 21, I worked for a company where I had to write rejection letters, and I remember writing one to someone with an Oxford degree. I was 21. They were no better off than I was, but I was that much younger.

Do you see scrapes and things going wrong as part of life’s learning? They’re essential, my god! My little mantra is that there’s no such thing as failure. When things go wrong it’s part of a brilliant learning curve. They’re also a test of your resolve.

What was your first test? I wanted to be an actress, but I was in an all-girls’ school, always playing the blokes because I was tall. I bandaged my chest and wore a moustache. I decided before I tried for drama school that I’d see if I could get into the National Youth Theatre. I went for an audition. I did a piece from Cymbelline and one from Educating Rita with the worse Scouse accent. I thought, ‘This is it.’ And then I didn’t get in and therefore thought, ‘Oh, so I’m clearly not very good.’ ‘It was a reality check, and I realised I needed to think of something else to do.

Sometimes, trying things out and them not working isn’t a bad failure. It’s hard not to feel knocked back but, actually, stopping can be a stepping stone. The only way to get through life is to fail – it gives you the tools to cope. Even in the most charmed life there will be a sticking-up paving stone.

So many young people are trying to live manicured, curated lives. They think they have to look and behave a certain way because of social media, but the difficulties are part of glorious life.

We’re trying to make everyone so risk averse and padded from the realities of life that people don’t see the difficulties and unpleasantness. It’s like trying to spray everything with air freshener.

What makes you good at presenting? For me, stories were always interesting. I’m fantastically nosy. I have no qualms about asking anyone anything, so being a researcher was the best job ever. Now I’m a presenter I just stand in a different place.

Do you see farming as a vocation? Yes, but I say it with a big caveat: I would never call myself a farmer. I work alongside a brilliant farmer called Tim. I don’t make a living out of producing food for other people, and that’s an important difference. To a farmer I’m someone who plays at it. I can inject a sheep, I can muck out and shovel shit all day, but I’m not dependent on it.

What about what Jeremy Clarkson’s been doing on his farm in the Cotswolds? Do you think his programme has helped people understand the challenges farmers face? Clarkson’s Farm is unequivocally brilliant because he shows how it really is, whereas with my progammes I’m talking to people who are, generally, educated already. The audiences are so different. Clarkson has helped to educate people who don’t think about where food comes from, who don’t know or care how the land is used.

What lessons did you learn when you first started farming? When we took on our four-acre smallholding (the farm is down the road), I realised, quickly, the enormous privilege it is to be the guardian of a piece of land. You don’t own it; it owns your arse. You spend your life trying to do the right thing by it. That’s the legacy that matters – the imprint you leave on the earth when you’ve gone. And that’s more true now than ever. Whether it’s a garden, smallholding, farm or national park, that legacy is hugely important for our future.

I remember when I went to see the farm (we wanted to keep sheep), someone told me about a place down the road, where the farmers who’d been on it were retiring. They’d been on that farm for 33 years as council tenants – there aren’t so many of those now. When you’re a tenant you have a year to get off the farm. The council were round with their clipboards, talking about splitting the farm up, selling the land and so on. The tenants who were leaving were devastated. When I went to see them, I sat in their kitchen and had an inkling of understanding because of my four acres. They’d been through foot and mouth, blue tongue and all manner of hell, but those 100 acres of difficult Wye Valley landscape had supported them, they’d raised their family there, and their legacy was going to be destroyed. It was heartbreaking. ‘We can’t bear what’s going to happen to the place we’ve looked after,’ they told me, and I understood why. The council weren’t doing anything wrong, but it was their disregard for the life’s work of those people that was devastating.

Was it easy for you to take over the land? Far from it… It took six months just to get a meeting, 2.5 years to achieve it. I cried pretty much every day. For 18 months the farm lay rotting, the house was uninhabitable, everything was falling down. Our intention was for it to remain a tenanted farm. There are so many people who farm for a living but would never be able to afford to buy the land.

What were the frustrations when you were starting out? All I wanted was to do my bit as well as possible, but there was nowhere to learn. I only knew what to do with sheep because I’d done the programme Lambing Live. Our hope was to turn it into a rural school. We had a partnership with farmer Tim and Sarah, who were running the farm.

As landlords we were responsible for the infrastructure so the farm could stay intact. We needed to be able to bring in a living for Tim and Sarah – he became the most brilliant teacher; we did the lambing courses together (the badly behaved animals with names were mine!).

Thoughts on rewilding? When you’re starting with a landscape that’s already been so affected by human behaviour it’s not going to become a wilderness overnight. It’s a partnership between humans and nature. We’ve messed up nature. We have to help nature back on course.

Is there an experience you can pinpoint that’s shaped your thinking when it comes to nature? One of the greatest privileges of my life was going to Yellowstone National Park. Wolves were reintroduced there 30 years ago, and that gave Yellowstone the full complement of species, from apex predators right down to the bugs at the bottom of the food chain. It became the biggest intact eco system in the world.

Reintroducing the wolves was like putting back one of nature’s essential cogs. It’s beautiful. But to say that would be the answer in the UK would be madness. The problem, exacerbated by social media, is the belief that ‘one size fits all’, whereas there has to be nuance. Removing all grazing animals is not the answer.

From the field to the kitchen… What type of cook are you? I love cooking but I don’t like faff, and I don’t like having to be too prescriptive. A recipe shouldn’t be rules; it’s just a collection of ideas. I like food that’s simple: if you start with good ingredients, you don’t need to muck about with them much.

Do you have a favourite recipe in the book? I love all of them! They’re all inspired by the makers and growers we’ve featured. One that springs to mind is the courgette gratin (p97) inspired by Gill Thompson (above) at Stych Farm Studios, who’s a platemaker. When she described the recipe to me I tried to re-create it in my own kitchen. It’s a combination of her ideas and mine – a wonderful collaborative recipe and a legacy recipe. What appealed to me was the way Gill described cooking the gratin – it’s a slow and thoughtful process, yet there’s no standing over it. You can drink tea and do something else while your courgettes are melting into a delicious mush. It’s proper comfort food, too, and one I know I’ll be cooking for years.

A note from KB… I’ve made this recipe twice as talking to Kate coincided with being given a pile of the last crop of courgettes from a friend’s garden. The gratin is excellent: full of flavour, satisfying and comforting. And continuing Kate’s tradition of recipe evolution, the second time I made it I stirred in half a jar of good quality borlotti beans for extra protein. Oh – and I sprinkled the top with some panko breadcrumbs lurking in the cupboard as I’d run out of bread. The result was great, but either way it’s a recipe I’ll be making regularly when summer rolls round again.

Kate’s book, Home Made – Recipes from the Countryside, is out now (Gaia, £26). Photographs: Andrew Montgomery. Home economist: Anna (Pooch) Horsburgh.

Read on for Kate’s magic list of Joyous Things – my favourite to date. It includes her favourite places to eat out, where she shops, what she’s reading, who she’d love to invite to dinner, what she’s reading, her views on music in the kitchen and her food manifesto (spoiler: fine dining isn’t part of it).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to KB's Joyous Things to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.